| Yeast |

“Now I’m going to visit my oldest friend. Kimoto, how are you!” |

|

|

| Kimoto |

“Hey, Yeast, are you doing fine, too?” |

| Yeast |

“Today I’ve lots of questions for you.” |

| Kimoto |

“No problem! My official name is Honjozo Kimoto. At Daishichi, I’m called just ‘Kimoto.’ I’m the oldest member of the kimoto series and I was born in 1982.” |

| Yeast |

“How was Daishichi doing at that time?” |

| Kimoto |

“Of course the kimoto method has existed for many centuries. It was so to speak the secret ingredient of Daishichi. Thanks to the local sake (jizake) boom of those years, I could finally come out as an independent product.” |

| Yeast |

“Your appearance must have caused a sensation at the time that the old grading system was still in use, with only special class, first class and second class sakes.” |

| Kimoto |

“Indeed. People finally discovered what ‘real taste’ was, as they often told me. Afterward, my family grew with junmai sake and junmai ginjo sake, but there are still many fans who specifically ask for me.” |

| Yeast |

“There are many people who think you are not ‘just’ a honjozo, if you permit me to say this. In the period that the production of ginjo sake finally took off, you became a brilliant long-seller!” |

| Kimoto |

“Yes, that was fun. Consumers first tend to look at figures such as the rice polishing ratio, but numbers don’t determine whether a sake is delicious or not: it wholly depends on the amount of care given during the brewing process. To polish the rice carefully and evenly, to steam it firmly with the use of traditional cast iron vats, and have a skillful master brewer prepare the koji - it’s the quality of the work in the brewery that counts.” |

| Yeast |

“Sure, that’s completely different from entrusting the whole process to machines. On top of that, there is also the complex and difficult job of making the kimoto starter mash.” |

| Kimoto |

“At Daishichi, we make every winter more than a hundred batches of kimoto sake. In other words, in one winter our brewers make more batches of kimoto sake than other brewers in their whole life. That amounts to an immense difference in experience.” |

| Yeast |

“Now I understand why you are so confident! Daishichi is also particular about the ingredients, isn’t it?” |

| Kimoto |

“Yes, for the brewer’s alcohol that Daishichi adds to me, it only uses alcohol made from rice. Daishichi holds on to the fundamental principle that sake should only be made from rice.” |

| Yeast |

“I like that kind of stubbornness! No deviation from the standard!” |

| Kimoto |

“Although I now have given up my position to Junmai Kimoto, for a long time I used to be the prop and pillar of Daishichi. I want people to reconsider the basic potential of sake. Cold sake in summer, warm sake in winter, and in autumn the seasonal Hiya-oroshi sake, there are many different ways to enjoy sake.” |

| Yeast |

“That’s how it is! I hear you’re also popular overseas as the standard of kimoto sake.” |

| Kimoto |

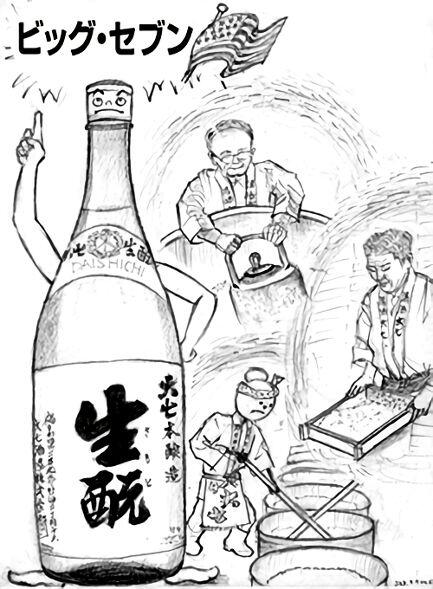

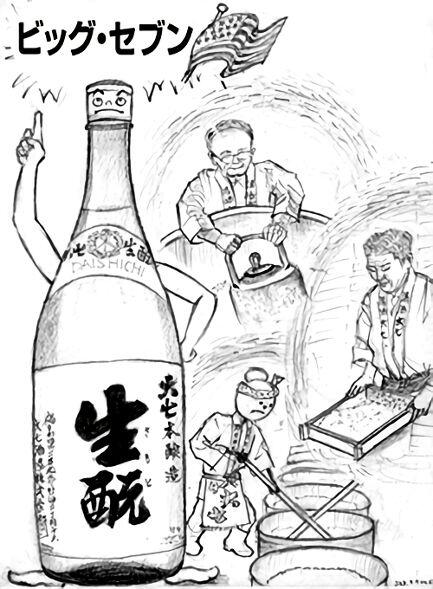

“Yes, in the United States I am the driving force behind Daishichi’s success. American customers today also remember the term kimoto. But of course the nickname ‘Big Seven’ is even more familiar to them.” |

| Yeast |

“Which dishes do you fit to, Big Seven?” |

| Kimoto |

“My range is very broad, but I could especially mention foods with a firm flavor, or foods with a creamy umami. Tempura and conger eel, roast chicken, meunière of white fish.” |

| Yeast |

“Could you finally tell me how one can best enjoy the seasonal sake Hiya-oroshi, which comes out in autumn?” |

| Kimoto |

“In Hiya-oroshi, freshness and maturity go miraculously together. When drunk cold, it should be at a cool room temperature, when warm it is best just slightly heated. Serve it with seasonal dishes.” |

| Yeast |

“That sounds delicious! Thanks for telling me such a lot today.” |