Episode No 1

The well

Daishichi’s brewing water is clear spring water that has passed through several layers of granite at the foot of Mt Adatara. It gushes up from three wells on the premises of the brewery, and one of these, called “Naka Ido” (Middle Well), has since our foundation been used to supply our brewing water. The shallow well has a depth of about 10 meter and the water, which contains a moderate amount of minerals, is semi-hard – in other words, it combines the delicacy of soft water with the fitness for maturation of hard water. It is excellent brewing water that is eminently suited to the kimoto method.

The pulley on the photo is used for the wakamizu-tori ritual, during which the first water of the year is drawn up at dawn on January 1.(Behind the well you can see the fune press used for pressing top-quality sake.)

Episode No 2

Japanese cast iron cauldrons

The merit of Japanese cast iron cauldrons (wagama) is that they can withstand the fierce boiling caused by a strong fire, which produces dry steam hotter than the boiling point of 100 degrees (“superheated steam”). This results in steamed rice that is hard on the outside and soft on the inside. Daishichi has always had a preference for the strong steam produced by Japanese cast iron cauldrons, and used to employ large Sanshu cauldrons. Also in the new brewery we started building in 2001, we have set up two fireplaces and large chimneys so that we could continue using Japanese cast iron cauldrons. This has been called the last great furnace construction in the sake world. And in 2009 we had, for the first time in 40 years in the whole of Japan, two new iron cauldrons cast. The new cauldrons were made in Iwate Prefecture, known for its tradition of Nanbu ironware. The new cauldrons possess a better heat conductivity and are stronger than the previous ones and will hopefully support our sake brewing for many years to come.

Episode No 3

Four koji rooms

Daishichi has four koji rooms. This is not in order to make a division per product – all our products contain koji made in all four rooms. We divide the rooms in moto-koji (koji for the yeast culture), soe-koji (koji for the first filling of the brewing tank), naka-koji (koji for the second filling of the brewing tank) and tome-koji (koji for the third filling of the brewing tank). The reason is that, ideally, the four batches of koji used for one bottle of sake should possesses subtle differences. For example, the moto-koji that is used for the initial yeast culture, must be able to provide lots of nurture to the fast growing and hungry yeast. Therefore koji with a strong enzymatic activity has to be slowly cultivated in an environment that is relatively humid. On the other hand, the last tome-koji that is directly related to the taste of the sake, must be a tsukihaze koji (i.e. the koji growing in spots on the surface of the grains) with a graceful fragrance, cultivated in a dry but warm environment. As the ideal environment for each type of koji is different, it is unavoidable that one has to make compromises when using just one koji room. Therefore, already for 60 years, Daishichi has been using four different koji rooms where temperature and humidity can each be individually controlled. Daishichi is the only sake brewery that uses such an extravagant way of koji making.

Episode No 4

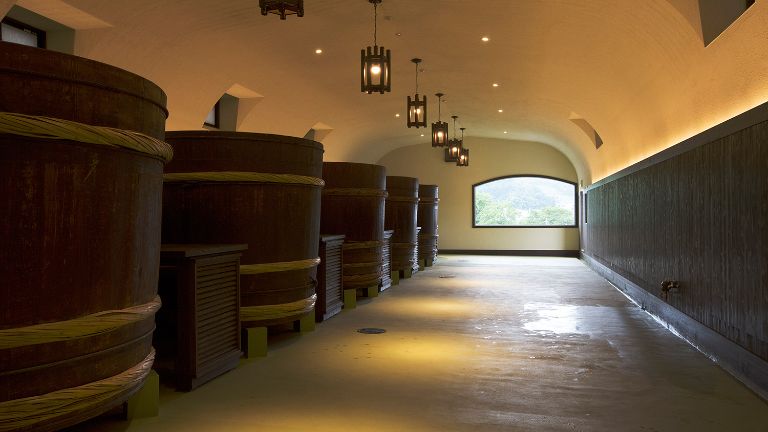

Brewing in wooden vats

After a gap of half a century, in 2001 Daishichi has resumed brewing some of its sake in traditional wooden vats (ki-oke). And in 2015 we have built a dedicated, beautiful facility for ki-oke brewing, something which is quite unique in the whole country. On a platform along the wall five wooden brewing vats rise up majestically, each of which is able to produce 30 koku (5,400 liter) of sake. The plastered vaulted ceiling is lighted beautifully by indirect lights and in the middle hang 7 lamps with wooden frames of original design. At the end of the room a large window affords a view of the Adatara mountain range. With this brewing room we aspire to the most extravagant sake brewing in the world: sake brewing that is not stingy about time. Time is a resource we all possess in equal measure and even kings cannot make it go faster. Our aim is a sake that is both complex and well-balanced, and that is top class sake without being a ginjo. We push on toward a great sake of real power.

Episode No 5

Maturation

Many sakes degrade with the passage of time. A sake that on the contrary grows more delicious, that receives the gift of matured umami from Time, is the only sake possessing real power. The matured deliciousness that only Time can bestow, is something that surpasses human wisdom. In order to make sake that can pass the test of time, at Daishichi we brew our sake carefully by hand in an artisanal way, without any shortcuts.

Our junmai and honjozo sakes spend one or more years in a maturation tank that is also cool in summer, and our junmai ginjo and junmai daiginjo sakes are after a strict inspection bottled in the spring of the year in which they were brewed and then allowed to rest in a refrigerated cellar. Here they spend one to several years. This cellar with top class sakes is so to speak Daishichi’s treasury. Special vintage sakes are matured several years longer than normal before being released as rare limited editions. The brewing year indicated on our back labels expresses the pride we feel in the fact that maturation is an added value of Daishichi.

Episode No 6

Chief Blender

Customers often ask us: “Is there any difference in the final quality of sake according to the brewing year or tank from which the sake comes?” As sake is produced by the working of living micro-organisms, of course there are small individual differences between the brewing tanks. And when the raw sake is stored, other differences occur according to how the maturation per tank progresses. To grasp those differences and create products that are always stable in taste is the task of our blender.

The chief blender of Daishichi is Keiko Okuda, the head of our research laboratory. Keiko Okuda has earned the qualification of “Sake Expert Assessor” from the National Research Institute of Brewing (being one of only about 100 persons to obtain this difficult distinction). She is exceptional not only in her knowledge of the present taste, maturation and future growth possibilities of our stored sake stock, but she also knows exactly which taste will be the result of blending one tank with another, as a musician who can hear the music when only reading the score.

When blending, 1+1 can become 3 or even 4, it is a second way of creation. It is a very creative task - without Keiko Okuda we would not be able to produce our Myoka Rangyoku Grande Cuvée, which is born from the ultimate drops of tens of different vintages.

Episode No 7

Contemporary Master Craftsman

In our final episode, we present the top of the bill: our master brewer Takanobu Sato, the No 1 kimoto brewer in Japan, with the title “Contemporary Master Craftsman.” Mr Sato was scouted by Katsuji Ito, our great toji of the Showa period, and already became kashira (deputy toji) in his second year, as he soon demonstrated his skills. In the autumn of 1997 he became master brewer after the sudden death of Kindaichi, the previous toji. Normally, the master brewer manages the whole operation by giving the other brewers specialized tasks, but Mr Sato’s way of working is different. While overseeing everything, he himself takes care of the kimoto culture that is the key to our sake brewing, thus acting as a sort of “player-manager.” He never stands still, but is constantly doing all sorts of tests and inspections, every year advancing in his research.

“It is simple: what decides the quality of the sake is whether you do 10 tasks perfectly or only 3.”

Master brewer Sato never takes any shortcuts. Thanks to the perfectionism of toji Sato, who fastidiously completes every process the right way through to the end, it was possible to realize the monumental and unprecedented achievement of twice winning the gold medal at the Japan Sake Awards with junmai sakes made with the kimoto method. Now he has graduated from the Sake Awards with their new sake and is putting all his strength in sake making of a more generous scale, letting large flowers bloom through longer maturation.

Incidentally, we can add that toji Sato with his own hands expertly fashions such tools as the wooden boxes for koji making (koji-buta) or the paddle-like stirring implements (kaibo), as well as the sakabayashi (sugidama), the cedar ball that announces that the new sake has been pressed – he even makes the round rice cakes offered at the New year! This is typical of our master brewer Takanobu Sato, who truly is the emblematic craftsman.